Fishes

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia| Fish Fossil range: Ordovician–Recent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A giant grouper at the Georgia Aquarium, seen swimming among schools of other fish

The ornate red lionfish as seen from a head-on view

| ||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||

| ||||||

| Included groups | ||||||

| Excluded groups | ||||||

A fish is any member of a paraphyletic group of organisms that consist of all gill-bearing aquatic craniate animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish, as well as various extinct related groups. Most fish are ectothermic ("cold-blooded"), allowing their body temperatures to vary as ambient temperatures change, though some of the large active swimmers like white shark and tuna can hold a higher core temperature.[1][2] Fish are abundant in most bodies of water. They can be found in nearly all aquatic environments, from high mountain streams (e.g., char and gudgeon) to the abyssal and even hadal depths of the deepest oceans (e.g., gulpers and anglerfish). At 32,000 species, fish exhibit greater species diversity than any other group of vertebrates.[3]

Fish are an important resource worldwide, especially as food. Commercial and subsistence fishers hunt fish in wild fisheries (see fishing) or farm them in ponds or in cages in the ocean (see aquaculture). They are also caught by recreational fishers, kept as pets, raised by fishkeepers, and exhibited in public aquaria. Fish have had a role in culture through the ages, serving as deities, religious symbols, and as the subjects of art, books and movies.

Because the term "fish" is defined negatively, and excludes the tetrapods (i.e., the amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals) which descend from within the same ancestry, it is paraphyletic, and is not considered a proper grouping in systematic biology. The traditional term pisces (also ichthyes) is considered a typological, but not a phylogenetic classification.

The earliest organisms that can be classified as fish were soft-bodied chordates that first appeared during the Cambrian period. Although they lacked a true spine, they possessed notochords which allowed them to be more agile than their invertebrate counterparts. Fish would continue to evolve through the Paleozoic era, diversifying into a wide variety of forms. Many fish of the Paleozoic developed external armor that protected them from predators. The first fish with jaws appeared in the Silurian period, after which many (such as sharks) became formidable marine predators rather than just the prey of arthropods.

Diversity of fish

Fish come in many shapes and sizes. This is a sea dragon, a close relative of the seahorse. Their leaf-like appendages enable them to blend in with floating seaweed.

Main article: Diversity of fish

The term "fish" most precisely describes any non-tetrapod craniate (i.e. an animal with a skull and in most cases a backbone) that has gills throughout life and whose limbs, if any, are in the shape of fins.[4] Unlike groupings such as birds or mammals, fish are not a single clade but a paraphyletic collection of taxa, including hagfishes, lampreys, sharks and rays, ray-finned fish, coelacanths, and lungfish.[5][6] Indeed, lungfish and coelacanths are closer relatives of tetrapods (such as mammals, birds, amphibians, etc.) than of other fish such as ray-finned fish or sharks, so the last common ancestor of all fish is also an ancestor to tetrapods. As paraphyletic groups are no longer recognised in modern systematic biology, the use of the term "fish" as a biological group must be avoided.

Many types of aquatic animals commonly referred to as "fish" are not fish in the sense given above; examples include shellfish, cuttlefish, starfish, crayfish and jellyfish. In earlier times, even biologists did not make a distinction – sixteenth century natural historians classified also seals, whales, amphibians, crocodiles, even hippopotamuses, as well as a host of aquatic invertebrates, as fish.[7] However, according the definition above, all mammals, including cetaceans like whales and dolphins, are not fish. In some contexts, especially in aquaculture, the true fish are referred to as finfish (or fin fish) to distinguish them from these other animals.

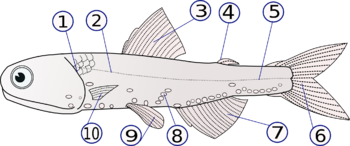

A typical fish is ectothermic, has a streamlined body for rapid swimming, extracts oxygen from water using gills or uses an accessory breathing organ to breathe atmospheric oxygen, has two sets of paired fins, usually one or two (rarely three) dorsal fins, an anal fin, and a tail fin, has jaws, has skin that is usually covered with scales, and lays eggs.

Each criterion has exceptions. Tuna, swordfish, and some species of sharks show some warm-blooded adaptations—they can heat their bodies significantly above ambient water temperature.[5] Streamlining and swimming performance varies from fish such as tuna, salmon, and jacks that can cover 10–20 body-lengths per second to species such as eels and rays that swim no more than 0.5 body-lengths per second.[5] Many groups of freshwater fish extract oxygen from the air as well as from the water using a variety of different structures. Lungfish have paired lungs similar to those of tetrapods, gouramis have a structure called the labyrinth organ that performs a similar function, while many catfish, such as Corydoras extract oxygen via the intestine or stomach.[8] Body shape and the arrangement of the fins is highly variable, covering such seemingly un-fishlike forms as seahorses, pufferfish, anglerfish, and gulpers. Similarly, the surface of the skin may be naked (as in moray eels), or covered with scales of a variety of different types usually defined as placoid (typical of sharks and rays), cosmoid (fossil lungfish and coelacanths), ganoid (various fossil fish but also living gars and bichirs), cycloid, and ctenoid (these last two are found on most bony fish).[9] There are even fish that live mostly on land. Mudskippers feed and interact with one another on mudflats and go underwater to hide in their burrows.[10] The catfish Phreatobius cisternarum lives in underground, phreatic habitats, and a relative lives in waterlogged leaf litter.[11][12]

Fish range in size from the huge 16-metre (52 ft) whale shark to the tiny 8-millimetre (0.3 in) stout infantfish.

Fish species diversity is roughly divided equally between marine (oceanic) and freshwater ecosystems. Coral reefs in the Indo-Pacific constitute the center of diversity for marine fishes, whereas continental freshwater fishes are most diverse in large river basins of tropical rainforests, especially the Amazon, Congo, and Mekong basins. More than 5,600 fish species inhabit Neotropical freshwaters alone, such that Neotropical fishes represent about 10% of all vertebrate species on the Earth.

Taxonomy

Fish are a paraphyletic group: that is, any clade containing all fish also contains the tetrapods, which are not fish. For this reason, groups such as the "Class Pisces" seen in older reference works are no longer used in formal classifications.

Traditional classification divide fish into three extant classes, and with extinct forms sometimes classified within the tree, sometimes as their own classes:[13][14]

- Class Agnatha (jawless fish)

- Subclass Cyclostomata (hagfish and lampreys)

- Subclass Ostracodermi (armoured jawless fish) †

- Class Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fish)

- Subclass Elasmobranchii (sharks and rays)

- Subclass Holocephali (chimaeras and extinct relatives)

- Class Placodermi (armoured fish) †

- Class Acanthodii ("spiny sharks", sometimes classified under bony fishes)†

- Class Osteichthyes (bony fish)

- Subclass Actinopterygii (ray finned fishes)

- Subclass Sarcopterygii (fleshy finned fishes, ancestors of tetrapods)

- Class Myxini (hagfish)

- Class Pteraspidomorphi † (early jawless fish)

- Class Thelodonti †

- Class Anaspida †

- Class Petromyzontida or Hyperoartia

- Petromyzontidae (lampreys)

- Class Conodonta (conodonts) †

- Class Cephalaspidomorphi † (early jawless fish)

- (unranked) Galeaspida †

- (unranked) Pituriaspida †

- (unranked) Osteostraci †

- Infraphylum Gnathostomata (jawed vertebrates)

- Class Placodermi † (armoured fish)

- Class Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fish)

- Class Acanthodii † (spiny sharks)

- Superclass Osteichthyes (bony fish)

- Class Actinopterygii (ray-finned fish)

- Subclass Chondrostei

- Order Acipenseriformes (sturgeons and paddlefishes)

- Order Polypteriformes (reedfishes and bichirs).

- Subclass Neopterygii

- Subclass Chondrostei

- Class Sarcopterygii (lobe-finned fish)

- Subclass Actinistia (coelacanths)

- Subclass Dipnoi (lungfish)

- Class Actinopterygii (ray-finned fish)

Some palaeontologists contend that because Conodonta are chordates, they are primitive fish. For a fuller treatment of this taxonomy, see the vertebrate article.

The position of hagfish in the phylum chordata is not settled. Phylogenetic research in 1998 and 1999 supported the idea that the hagfish and the lampreys form a natural group, the Cyclostomata, that is a sister group of the Gnathostomata.[15][16]

The various fish groups account for more than half of vertebrate species. There are almost 28,000 known extant species, of which almost 27,000 are bony fish, with 970 sharks, rays, and chimeras and about 108 hagfish and lampreys.[17] A third of these species fall within the nine largest families; from largest to smallest, these families are Cyprinidae, Gobiidae, Cichlidae, Characidae, Loricariidae, Balitoridae, Serranidae, Labridae, and Scorpaenidae. About 64 families are monotypic, containing only one species. The final total of extant species may grow to exceed 32,500.[18]

Anatomy

Main article: Fish anatomy

Respiration

Most fish exchange gases using gills on either side of the pharynx. Gills consist of threadlike structures called filaments. Each filament contains a capillary network that provides a large surface area for exchanging oxygen and carbon dioxide. Fish exchange gases by pulling oxygen-rich water through their mouths and pumping it over their gills. In some fish, capillary blood flows in the opposite direction to the water, causing countercurrent exchange. The gills push the oxygen-poor water out through openings in the sides of the pharynx. Some fish, like sharks and lampreys, possess multiple gill openings. However, bony fish have a single gill opening on each side. This opening is hidden beneath a protective bony cover called an operculum.Juvenile bichirs have external gills, a very primitive feature that they share with larval amphibians.

Fish from multiple groups can live out of the water for extended time periods. Amphibious fish such as the mudskipper can live and move about on land for up to several days, or live in stagnant or otherwise oxygen depleted water. Many such fish can breathe air via a variety of mechanisms. The skin of anguillid eels may absorb oxygen directly. The buccal cavity of the electric eel may breathe air. Catfish of the families Loricariidae, Callichthyidae, and Scoloplacidae absorb air through their digestive tracts.[19] Lungfish, with the exception of the Australian lungfish, and bichirs have paired lungs similar to those of tetrapods and must surface to gulp fresh air through the mouth and pass spent air out through the gills. Gar and bowfin have a vascularized swim bladder that functions in the same way. Loaches, trahiras, and many catfish breathe by passing air through the gut. Mudskippers breathe by absorbing oxygen across the skin (similar to frogs). A number of fish have evolved so-called accessory breathing organs that extract oxygen from the air. Labyrinth fish (such as gouramis and bettas) have a labyrinth organ above the gills that performs this function. A few other fish have structures resembling labyrinth organs in form and function, most notably snakeheads, pikeheads, and the Clariidae catfish family.

Breathing air is primarily of use to fish that inhabit shallow, seasonally variable waters where the water's oxygen concentration may seasonally decline. Fish dependent solely on dissolved oxygen, such as perch and cichlids, quickly suffocate, while air-breathers survive for much longer, in some cases in water that is little more than wet mud. At the most extreme, some air-breathing fish are able to survive in damp burrows for weeks without water, entering a state of aestivation (summertime hibernation) until water returns.

Tuna gills inside of the head. The fish head is oriented snout-downwards, with the view looking towards the mouth.

Circulation

Fish have a closed-loop circulatory system. The heart pumps the blood in a single loop throughout the body. In most fish, the heart consists of four parts, including two chambers and an entrance and exit.[20] The first part is the sinus venosus, a thin-walled sac that collects blood from the fish's veins before allowing it to flow to the second part, the atrium, which is a large muscular chamber. The atrium serves as a one-way antechamber, sends blood to the third part, ventricle. The ventricle is another thick-walled, muscular chamber and it pumps the blood, first to the fourth part, bulbus arteriosus, a large tube, and then out of the heart. The bulbus arteriosus connects to the aorta, through which blood flows to the gills for oxygenation.Digestion

Jaws allow fish to eat a wide variety of food, including plants and other organisms. Fish ingest food through the mouth and break it down in the esophagus. In the stomach, food is further digested and, in many fish, processed in finger-shaped pouches called pyloric caeca, which secrete digestive enzymes and absorb nutrients. Organs such as the liver and pancreas add enzymes and various chemicals as the food moves through the digestive tract. The intestine completes the process of digestion and nutrient absorption.Excretion

As with many aquatic animals, most fish release their nitrogenous wastes as ammonia. Some of the wastes diffuse through the gills. Blood wastes are filtered by the kidneys.Saltwater fish tend to lose water because of osmosis. Their kidneys return water to the body. The reverse happens in freshwater fish: they tend to gain water osmotically. Their kidneys produce dilute urine for excretion. Some fish have specially adapted kidneys that vary in function, allowing them to move from freshwater to saltwater.

Scales

Main article: Scale (zoology)#Fish scales

The scales of fish originate from the mesoderm (skin); they may be similar in structure to teeth.Sensory and nervous system

Central nervous system

Fish typically have quite small brains relative to body size compared with other vertebrates, typically one-fifteenth the brain mass of a similarly sized bird or mammal.[21] However, some fish have relatively large brains, most notably mormyrids and sharks, which have brains about as massive relative to body weight as birds and marsupials.[22]Fish brains are divided into several regions. At the front are the olfactory lobes, a pair of structures that receive and process signals from the nostrils via the two olfactory nerves.[21] The olfactory lobes are very large in fish that hunt primarily by smell, such as hagfish, sharks, and catfish. Behind the olfactory lobes is the two-lobed telencephalon, the structural equivalent to the cerebrum in higher vertebrates. In fish the telencephalon is concerned mostly with olfaction.[21] Together these structures form the forebrain.

Connecting the forebrain to the midbrain is the diencephalon (in the diagram, this structure is below the optic lobes and consequently not visible). The diencephalon performs functions associated with hormones and homeostasis.[21] The pineal body lies just above the diencephalon. This structure detects light, maintains circadian rhythms, and controls color changes.[21]

The midbrain or mesencephalon contains the two optic lobes. These are very large in species that hunt by sight, such as rainbow trout and cichlids.[21]

The hindbrain or metencephalon is particularly involved in swimming and balance.[21] The cerebellum is a single-lobed structure that is typically the biggest part of the brain.[21] Hagfish and lampreys have relatively small cerebellae, while the mormyrid cerebellum is massive and apparently involved in their electrical sense.[21]

The brain stem or myelencephalon is the brain's posterior.[21] As well as controlling some muscles and body organs, in bony fish at least, the brain stem governs respiration and osmoregulation.[21]

Sense organs

Most fish possess highly developed sense organs. Nearly all daylight fish have color vision that is at least as good as a human's (see vision in fishes). Many fish also have chemoreceptors that are responsible for extraordinary senses of taste and smell. Although they have ears, many fish may not hear very well. Most fish have sensitive receptors that form the lateral line system, which detects gentle currents and vibrations, and senses the motion of nearby fish and prey.[23] Some fish, such as catfish and sharks, have organs that detect weak electric currents on the order of millivolt.[24] Other fish, like the South American electric fishes Gymnotiformes, can produce weak electric currents, which they use in navigation and social communication.Fish orient themselves using landmarks and may use mental maps based on multiple landmarks or symbols. Fish behavior in mazes reveals that they possess spatial memory and visual discrimination.[25]

Vision

Main article: Vision in fishes

Vision is an important sensory system for most species of fish. Fish eyes are similar to those of terrestrial vertebrates like birds and mammals, but have a more spherical lens. Their retinas generally have both rod cells and cone cells (for scotopic and photopic vision), and most species have colour vision. Some fish can see ultraviolet and some can see polarized light. Amongst jawless fish, the lamprey has well-developed eyes, while the hagfish has only primitive eyespots[disambiguation needed

Muscular system

Main article: Fish locomotion

Reproductive system

Further information: Spawn (biology)

Organs

Fish reproductive organs include testes and ovaries. In most species, gonads are paired organs of similar size, which can be partially or totally fused.[35] There may also be a range of secondary organs that increase reproductive fitness.In terms of spermatogonia distribution, the structure of teleosts testes has two types: in the most common, spermatogonia occur all along the seminiferous tubules, while in Atherinomorph fish they are confined to the distal portion of these structures. Fish can present cystic or semi-cystic spermatogenesis in relation to the release phase of germ cells in cysts to the seminiferous tubules lumen.[35]

Fish ovaries may be of three types: gymnovarian, secondary gymnovarian or cystovarian. In the first type, the oocytes are released directly into the coelomic cavity and then enter the ostium, then through the oviduct and are eliminated. Secondary gymnovarian ovaries shed ova into the coelom from which they go directly into the oviduct. In the third type, the oocytes are conveyed to the exterior through the oviduct.[36] Gymnovaries are the primitive condition found in lungfish, sturgeon, and bowfin. Cystovaries characterize most teleosts, where the ovary lumen has continuity with the oviduct.[35] Secondary gymnovaries are found in salmonids and a few other teleosts.

Oogonia development in teleosts fish varies according to the group, and the determination of oogenesis dynamics allows the understanding of maturation and fertilization processes. Changes in the nucleus, ooplasm, and the surrounding layers characterize the oocyte maturation process.[35]

Postovulatory follicles are structures formed after oocyte release; they do not have endocrine function, present a wide irregular lumen, and are rapidly reabsorbed in a process involving the apoptosis of follicular cells. A degenerative process called follicular atresia reabsorbs vitellogenic oocytes not spawned. This process can also occur, but less frequently, in oocytes in other development stages.[35]

Some fish are hermaphrodites, having both testes and ovaries either at different phases in their life cycle or, as in hamlets, have them simultaneously.

Reproductive method

Over 97% of all known fish are oviparous,[37] that is, the eggs develop outside the mother's body. Examples of oviparous fish include salmon, goldfish, cichlids, tuna, and eels. In the majority of these species, fertilisation takes place outside the mother's body, with the male and female fish shedding their gametes into the surrounding water. However, a few oviparous fish practice internal fertilization, with the male using some sort of intromittent organ to deliver sperm into the genital opening of the female, most notably the oviparous sharks, such as the horn shark, and oviparous rays, such as skates. In these cases, the male is equipped with a pair of modified pelvic fins known as claspers.Marine fish can produce high numbers of eggs which are often released into the open water column. The eggs have an average diameter of 1 millimetre (0.039 in).

- Egg of lamprey

- Egg of catshark (mermaids' purse)

- Egg of bullhead shark

- Egg of chimaera

In ovoviviparous fish the eggs develop inside the mother's body after internal fertilization but receive little or no nourishment directly from the mother, depending instead on the yolk. Each embryo develops in its own egg. Familiar examples of ovoviviparous fish include guppies, angel sharks, and coelacanths.

Some species of fish are viviparous. In such species the mother retains the eggs and nourishes the embryos. Typically, viviparous fish have a structure analogous to the placenta seen in mammals connecting the mother's blood supply with that of the embryo. Examples of viviparous fish include the surf-perches, splitfins, and lemon shark. Some viviparous fish exhibit oophagy, in which the developing embryos eat other eggs produced by the mother. This has been observed primarily among sharks, such as the shortfin mako and porbeagle, but is known for a few bony fish as well, such as the halfbeak Nomorhamphus ebrardtii.[38] Intrauterine cannibalism is an even more unusual mode of vivipary, in which the largest embryos eat weaker and smaller siblings. This behavior is also most commonly found among sharks, such as the grey nurse shark, but has also been reported for Nomorhamphus ebrardtii.[38]

Aquarists commonly refer to ovoviviparous and viviparous fish as livebearers.

Evolution

See also: prehistoric fish

Proliferation of fish was apparently due to the hinged jaw, because jawless fish left very few descendants.[51] Lampreys may approximate pre-jawed fish. The first jaws are found in Placodermi fossils. It is unclear if the advantage of a hinged jaw is greater biting force, improved respiration, or a combination of factors.

Fish may have evolved from a creature similar to a coral-like Sea squirt, whose larvae resemble primitive fish in important ways. The first ancestors of fish may have kept the larval form into adulthood (as some sea squirts do today), although perhaps the reverse is the case.

Conservation

The 2006 IUCN Red List names 1,173 fish species that are threatened with extinction.[52] Included are species such as Atlantic cod,[53] Devil's Hole pupfish,[54] coelacanths,[55] and great white sharks.[56] Because fish live underwater they are more difficult to study than terrestrial animals and plants, and information about fish populations is often lacking. However, freshwater fish seem particularly threatened because they often live in relatively small water bodies. For example, the Devil's Hole pupfish occupies only a single 3 by 6 metres (10 by 20 ft) pool.[57]Overfishing

Main article: Overfishing

Habitat destruction

See also: Environmental effects of fishing

A key stress on both freshwater and marine ecosystems is habitat degradation including water pollution, the building of dams, removal of water for use by humans, and the introduction of exotic species.[65] An example of a fish that has become endangered because of habitat change is the pallid sturgeon, a North American freshwater fish that lives in rivers damaged by human activity.[66]Exotic species

Introduction of non-native species has occurred in many habitats. One of the best studied examples is the introduction of Nile perch into Lake Victoria in the 1960s. Nile perch gradually exterminated the lake's 500 endemic cichlid species. Some of them survive now in captive breeding programmes, but others are probably extinct.[67] Carp, snakeheads,[68] tilapia, European perch, brown trout, rainbow trout, and sea lampreys are other examples of fish that have caused problems by being introduced into alien environments.Importance to humans

Culture

In the Book of Jonah a "great fish" swallowed Jonah the Prophet. Legends of half-human, half-fish mermaids have featured in stories like those of Hans Christian Andersen and movies like Splash (See Merman, Mermaid).Terminology

Shoal or school?

Main article: Shoaling and schooling

![Drawing of animal with large mouth, long tail, very small dorsal fins, and pectoral fins that attach towards the bottom of the body, resembling lizard legs in scale and development.[49]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/95/Dunkleosteus_BW.jpg/220px-Dunkleosteus_BW.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment