Fishing is the activity of trying to catch

fish. Fish are normally caught

in the wild.

Techniques for catching fish include

hand gathering,

spearing,

netting,

angling and

trapping.

The term fishing may be applied to catching other

aquatic animals such as

molluscs,

cephalopods,

crustaceans, and

echinoderms. The term is not normally applied to catching

farmed fish, or to

aquatic mammals, such as

whales, where the term

whaling is more appropriate.

According to

FAO statistics, the total number of

commercial fishermen and

fish farmers is estimated to be 38 million.

Fisheries and

aquaculture provide direct and indirect employment to over 500 million people.

[1] In 2005, the worldwide per capita consumption of fish captured from

wild fisheries was 14.4 kilograms, with an additional 7.4 kilograms harvested from

fish farms.

[2] In addition to providing food, modern fishing is also a

recreational pastime.

History

Fishing is an ancient practice that dates back to at least the beginning of the

Paleolithic period about 40,000 years ago.

[3] Isotopic analysis of the skeletal remains of

Tianyuan man, a 40,000 year old modern human from eastern Asia, has shown that he regularly consumed freshwater fish.

[4][5] Archaeology features such as

shell middens,

[6] discarded fish bones and

cave paintings show that sea foods were important for survival and consumed in significant quantities. During this period, most people lived a

hunter-gatherer lifestyle and were, of necessity, constantly on the move. However, where there are early examples of permanent settlements (though not necessarily permanently occupied) such as those at

Lepenski Vir, they are almost always associated with fishing as a major source of food.

The ancient

river Nile was full of fish; fresh and dried fish were a staple food for much of the population.

[7] The

Egyptians had implements and methods for fishing and these are illustrated in

tomb scenes, drawings, and

papyrus documents. Some representations hint at fishing being pursued as a pastime. In India, the

Pandyas, a classical

Dravidian Tamil kingdom, were known for the pearl fishery as early as the 1st century BC. Their seaport

Tuticorin was known for deep sea

pearl fishing. The

paravas, a Tamil caste centred in

Tuticorin, developed a rich community because of their pearl trade, navigation knowledge and fisheries. Fishing scenes are rarely represented in

ancient Greek culture, a reflection of the low social status of fishing. However,

Oppian of Corycus, a Greek author wrote a major treatise on sea fishing, the

Halieulica or

Halieutika, composed between 177 and 180. This is the earliest such work to have survived to the modern day. Pictorial evidence of

Roman fishing comes from

mosaics.

[8] The Greco-Roman sea god

Neptune is depicted as wielding a fishing trident. The

Moche people of ancient

Peru depicted fishermen in their ceramics.

[9]

One of the world’s longest trading histories is the

trade of dry cod from the

Lofoten area of

Norway to the southern parts of

Europe,

Italy, Spain and

Portugal. The trade in

cod started during the

Viking period or before, has been going on for more than 1,000 years and is still important.

[citation needed]

Techniques

There are many fishing techniques or methods for catching fish. The term can also be applied to methods for catching other

aquatic animals such as

molluscs (

shellfish,

squid,

octopus) and edible marine

invertebrates.

Fishing techniques include

hand gathering,

spearfishing,

netting,

angling and

trapping.

Recreational,

commercial and

artisanal fishers use different techniques, and also, sometimes, the same techniques. Recreational fishers fish for pleasure or sport, while commercial fishers fish for profit. Artisanal fishers use traditional, low-tech methods, for survival in third-world countries, and as a cultural heritage in other countries. Mostly, recreational fishers use angling methods and commercial fishers use netting methods.

There is an intricate link between various fishing techniques and knowledge about the fish and their behaviour including

migration,

foraging and

habitat. The effective use of fishing techniques often depends on this additional knowledge.

[10] Some fishermen follow

fishing folklores which claim that fish feeding patterns are influenced by the position of the sun and the moon.

Tackle

Main article:

Fishing tackle

Fishing tackle is a general term that refers to the equipment used by

fishermen when fishing.

Almost any equipment or gear used for fishing can be called fishing tackle. Some examples are

hooks,

lines,

sinkers,

floats,

rods,

reels,

baits,

lures,

spears,

nets,

gaffs,

traps,

waders and tackle boxes.

Tackle that is attached to the end of a

fishing line is called

terminal tackle. This includes

hooks,

sinkers,

floats, leaders,

swivels, split rings and wire, snaps, beads, spoons, blades, spinners and clevises to attach spinner blades to fishing lures.

Fishing tackle can be contrasted with

fishing techniques. Fishing tackle refers to the physical equipment that is used when fishing, whereas fishing techniques refers to the ways the tackle is used when fishing.

Fishing vessels

A fishing vessel is a

boat or

ship used to catch fish in the sea, or on a lake or river. Many different kinds of vessels are used in

commercial,

artisanal and

recreational fishing.

According to the

FAO, there are currently (2004) four million commercial fishing vessels.

[11] About 1.3 million of these are decked vessels with enclosed areas. Nearly all of these decked vessels are mechanised, and 40,000 of them are over 100 tons. At the other extreme, two-thirds (1.8 million) of the

undecked boats are traditional craft of various types, powered only by sail and oars.

[11] These boats are used by

artisan fishers.

It is difficult to estimate how many

recreational fishing boats there are, although the number is high. The term is fluid, since most recreational boats are also used for fishing from time to time. Unlike most commercial fishing vessels, recreational fishing boats are often not dedicated just to fishing. Just about anything that will stay afloat can be called a recreational fishing boat, so long as a

fisher periodically climbs aboard with the intent to catch a fish. Fish are caught for recreational purposes from boats which range from

dugout canoes,

kayaks,

rafts,

pontoon boats and small

dingies to

runabouts,

cabin cruisers and cruising yachts to large, hi-tech and luxurious

big game rigs.

[12] Larger boats, purpose-built with recreational fishing in mind, usually have large, open

cockpits at the

stern, designed for convenient fishing.

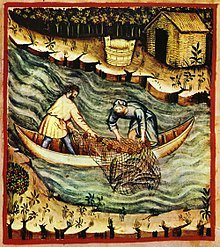

Traditional fishing

Traditional fishing is a term used to describe small scale

commercial or

subsistence fishing practices, using traditional techniques such as

rod and

tackle,

arrows and

harpoons,

throw nets and drag nets, etc.

Recreational fishing

Recreational and sport fishing describe fishing primarily for

pleasure or competition. Recreational fishing has conventions, rules, licensing restrictions and

laws that limit the way in which fish may be caught; typically, these prohibit the use of nets and the catching of fish with hooks not in the

mouth. The most common form of recreational fishing is done with a

rod,

reel,

line,

hooks and any one of a wide range of

baits or

lures such as

artificial flies. The practice of catching or attempting to catch fish with a hook is generally known as

angling. In angling, it is sometimes expected or required that fish be returned to the

water (

catch and release). Recreational or sport fishermen may log their catches or participate in fishing competitions.

Big-game fishing describes fishing from boats to catch large open-water species such as

tuna,

sharks and

marlin. Sport fishing (sometimes game fishing) describes recreational fishing where the primary reward is the challenge of finding and catching the fish rather than the

culinary or financial value of the fish's flesh. Fish sought after include

marlin,

tuna,

tarpon,

sailfish,

shark,

mackerel, and many others.

Fishing industry

The fishing industry includes any industry or activity concerned with taking, culturing, processing, preserving, storing, transporting, marketing or selling fish or fish products. It is defined by the

FAO as including

recreational,

subsistence and

commercial fishing, and the harvesting,

processing, and

marketing sectors.

[13] The commercial activity is aimed at the delivery of

fish and other

seafood products for human consumption or for use as

raw material in other industrial processes.

There are three principal industry sectors:

[14]

- The commercial sector comprises enterprises and individuals associated with wild-catch or aquaculture resources and the various transformations of those resources into products for sale. It is also referred to as the "seafood industry", although non-food items such as pearls are included among its products.

- The traditional sector comprises enterprises and individuals associated with fisheries resources from which aboriginal people derive products in accordance with their traditions.

- The recreational sector comprises enterprises and individuals associated for the purpose of recreation, sport or sustenance with fisheries resources from which products are derived that are not for sale.

Intensive koi aquaculture facility in Israel

A small number of species support the majority of the world’s fisheries. Some of these species are

herring,

cod,

anchovy,

tuna,

flounder,

mullet,

squid,

shrimp,

salmon,

crab,

lobster,

oyster and

scallops. All except these last four provided a worldwide catch of well over a

million tonnes in 1999, with

herring and

sardines together providing a catch of over 22 million metric tons in 1999. Many other species as well are fished in smaller numbers.

Fish farms

Fish farming is the principal form of

aquaculture, while other methods may fall under

mariculture. It involves raising fish commercially in tanks or enclosures, usually for food. A facility that releases juvenile fish into the wild for recreational fishing or to supplement a species' natural numbers is generally referred to as a fish

hatchery. Fish species raised by fish farms include

Atlantic salmon,

carp,

tilapia,

catfish,

trout and others.

Increased demands on

wild fisheries by

commercial fishing has caused widespread

overfishing. Fish farming offers an alternative solution to the increasing

market demand for

fish and fish

protein.

Gyula Derkovits, still-life with fish (1928)

Fish products

Fish and

fish products are

consumed as food all over the world. With other

seafoods, it provides the world's prime source of high-quality

protein: 14–16 percent of the animal protein consumed worldwide. Over one billion people rely on fish as their primary source of animal protein.

[15]

Fish and other aquatic organisms are also processed into various food and non-food products, such as sharkskin leather, pigments made from the inky secretions of

cuttlefish,

isinglass used for the

clarification of

wine and

beer,

fish emulsion used as a

fertilizer,

fish glue,

fish oil and

fish meal.

Fish are also collected live for research or the

aquarium trade.

Fish marketing

Fisheries management

Sustainability

Issues involved in the long term sustainability of fishing include

overfishing,

by-catch,

marine pollution,

environmental effects of fishing,

climate change and

fish farming.

Conservation issues are part of

marine conservation, and are addressed in

fisheries science programs. There is a growing gap between how many fish are available to be caught and humanity’s desire to catch them, a problem that gets worse as the

world population grows.

Similar to other

environmental issues, there can be conflict between the fishermen who depend on fishing for their livelihoods and

fishery scientists who realise that if future fish populations are to be

sustainable then some fisheries must limit fishing or cease operations.

Cultural impact

_NOAA.jpg)